Overview of North American Navions

Aviation Consumer

Volume 36, Number 3 , March 2006

North American Navion

A big, beefy retractable that traces its lineage to the P-51 Mustang. Although cheap to buy, watch for basketcase airframes needing expensive restoration.

Many Navions sport warbird paint, such as Case Ketting’s tip-tank-equipped, IO-540-powered version above.

In the world of general aviation, not many light aircraft can claim to have a genuine military pedigree, although a few have been tarted up to look like warbirds. One of the few non-pretenders is the Navion, introduced by North American Aviation in 1946 and intended to capitalize on what everyone assumed would be a post-war flying boom.

With its rakish sliding turtle-shell canopy, tall stalky gear and a P-51-style tail, the four-seat retractable came from the same stable as the Mustang, whose production ended at the close of the war. And true to its heritage, the Navion—pronounced “Navy-on”—did find a niche in military aviation as a liaison ride and many are still painted in military livery.

Although it came from the same company as the P-51, the Navion, was no Mustang, at least in per formance. Its cruising speed was a relatively leisurely 140 MPH and when Beechcraft appeared with the 175-MPH V-tail Bonanza in 1947, the Navion faced a stiff sales challenge. (Optional engine upgrades have caused the Navion to lose its rep as a slug.)

Although not many were made—about 2700 total—the airplane lasted all the way to 1976, having been manufactured by different companies in various models and incarnations.

Although it trailed the Bonanza in both production numbers and speed, the Navion had something the Bo lacked: A certain panache and a giant interior of the sort GM’s Ed Cole would have designed if he’d gotten hold of the Bonanza.

While owners concede the airplane is no Bendix racer, they prize it for its hell-for-strong construction. “The Navion,” one owner told us years ago, “is built with the war-effort idea that if a quarter-inch bolt will work, a half-inch bolt has got to be better.” In fact, Navion engineers used a monocoque structure for the wings and fuselage, believing this reduced weight and eliminated the possibility of concealed structural weakness with age. They may have never imagined how long the airplanes would be around.

Model History

One reason for the Navion’s beefy construction is that North American hoped to sell thousands to the military. But it didn’t happen. Only 250 were bought, but even at that, the services ordered enough spares to maintain these airplanes so that parts have generally not been a huge problem for owners.

The first Navion had a Continental 185-HP engine with a takeoff rating of 205 HP. After building 1100 of these airplanes, North American sold its rights in 1948 to Ryan of San Diego, the same Ryan that built the Spirit of St. Louis for Charles Lindbergh. Ryan dubbed their Navion the A model and built another 1200 before ceasing production three years later. Some of the later Ryan models had a 225-HP Continental E-225. (The last B model, which used a 260-HP geared Lycoming GO-435 engine, was the last model of the original genuine Navion.)

But that wasn’t to be the end of the Navion. It remained out of production until 1955, when rights were sold to Tubular Steel Corporation (TUSCO), which specialized in rebuilding and updating old Navions with Continental IO-470 engines of 240, 250 and 260 HP. These are known as the D, E and F models, respectively. TUSCO resumed production in 1958 and introduced some refinements. The sliding canopy was replaced with a door, fuel capacity was greatly increased and a 260-HP Continental was added. Thus was born the so-called Rangemaster G model. About 50 were built before hurricane Carla wiped out the factory in 1961.

Still, the Navion endured, thanks to the American Navion Society. Some of its members bought the Navion rights and in 1967, they began building a handful of Rangemaster H models, which had a 285-hp Continental IO-520 engine. But that company folded, too. Twice in the mid-1970s, there were attempts to revive the Rangemaster. Only a half-dozen or so airplanes were built.

Today, the type certificate and manufacturing jigs are owned by Sierra Hotel (listed below), which provides service and parts.

There are also a number of well-regarded mod shops that support the Navion and like a handful of other models, the type has an excellent owner organization in the American Navion Society. In short, the airplane is surprisingly well supported.

Market Scan, Performance

For the prospective buyer, the Navion immediately distinguishes itself in one respect: It ranks as one of the least expensive retractables on the market, according to the Aircraft Blue Book Price Digest. A late-model Rangemaster H can be had for about $70,000 and early models—still not bad choices—retail in the $40,000 range. But a potential buyer should go into the deal with eyes open. An older Navion may need a lot of work. The support is there, but you’ll still need to pay for it.

With an estimated 1400 on the U.S. registry, Navions may be hard to find. A recent issue of Trade-A-Plane showed a smattering of about a dozen, some North American models, some Ryan and a TUSCO or two. The prospective buyer should definitely hook up with The Navion Society before even considering a purchase.

To make up for its lackluster performance, many owners have modified and rebuilt their airplanes to a degree matched by few other models. It’s safe to say that most of the airplanes have been modified and you’ll need help from an expert to sort out what’s been done.

Early 205-HP Navions cruise at about 140 MPH on 11 GPH. The 225-HP versions add about 5 MPH to that number in exchange for a gallon more of fuel burn.

You’ll go about 155 MPH or so in the 240-, 250- and 260-HP second-generation D, E and F Navions.

In contrast, the 1951 B-model, with the geared 260-HP Lycoming, ranks as the most inefficient Navion built: It can manage only about 153 MPH on 13.1 GPH. Other low-priced used retractables such as the Comanche 180 and early Mooneys fly faster and use less fuel, but they’re also more expensive and lack the Navion’s expansive cabin comfort.

Writes owner Joe Noyes of Irvine, California, “My current Navion is a 1961 model G Rangemaster powered by a TCM IO-470-H engine of 260 HP…The engine is also equipped with GAMIjectors which have been fine tuned so that typical lean-of-peak true airspeeds at cruise altitudes are in the range of 155 to 158 MPH on 11.4 to 11.7 GPH.”

Takeoff performance varies by engine installation, of course, but this is generally one of the Navion’s selling points. According to early sales claims, the A model had a takeoff ground run of only 560 feet while Rangemasters hop off the pavement in 425 feet. However, so many airplanes have been upgraded with larger engines—all the way up to a Continental IO-550—that performance is all over the map. “The fat wing will still get off the ground in 600 to 1000 feet, depending upon engine, and cruise at 125 to 165 knots, again, depending on engine,” writes owner Case Ketting. In any case, the Navion is better than average at short field work and will get into short runways comfortably.

Payload, Comfort

Fuel capacity differs widely from one Navion to another, so it takes effort to pin down actual payload numbers. Although the basic fuel system has 40 gallons, many Navions have an extra 20-gallon tank under the rear seat or in the baggage compartment. Also, there are several different types of tip tanks available, which some owners say can yield a range of 1000 miles.

Late-model Rangemasters had fuel capacities of up to 108 gallons, although that much fuel would limit payload. Generally, expect still-air range of about 600 miles in an older Navion with 60-gallon tanks. This will be reduced somewhat as extra passengers and baggage are added.

Despite its beefy construction, the Navion weighs 1900 to 2000 pounds empty with a gross weight of either 2750 or 2850 pounds, giving it a useful load of around 800 pounds. The gross weight on the G Rangemasters can be as much as 3315 pounds. At the lower weights, with four people and 100 pounds of baggage, there isn’t a lot of room for fuel. The 260-HP version has a useful load just a little better than the A model’s. Unfortunately, it burns 20 percent more fuel, so on the same trip, the load would even be more limited.

More practical for longer trips are the re-engined D, E and F models, which have increased gross weights. For the typical 260-HP Rangemaster, the useful load is about 1200 pounds. This provides for decent range with four passengers and 100 pounds of luggage. Although not recommended, thanks to its fat wing, owners tell us the Rangemaster will take off and climb with about anything you can stuff into it.

And that turns out to be a lot. By any standards, the airplane is quite large, with an enormous cabin whose seating style is best described as regal. Once inside, passengers will be more comfortable than they would be in a Mooney or a Bonanza and with a better view. The rear seat is straight out of a 1950s sedan, a broad bench that will fit three people in acceptable comfort.

“The Navion’s spacious cabin allows passengers to move (carefully) from front to rear seats in flight. Try that in a Mooney!” writes owner John Leggatt. Up front, the panel is big and broad with good visibility forward and sideways, with a smattering of instruments and switches on the canopy overhead. Soundproofing wasn’t a priority in the 1940s, so unless owners have done their own soundproofing mods, the cabins tend to be noisy.

Mods

Many airframes that have been around for awhile have a long list of modifications. In the case of the Navion, the list is unusually long. Wrote one owner, “If you like Chinese menus, you’ll love the Navion.” Most Navions have been modified so much that our model comparisons charts have to be taken advisedly. Every airplane performs differently.

Speed modifications are not necessarily cumulative, as the American Navion Society has noted. For instance, a 5 MPH mod and a 3-MPH mod won’t necessarily produce an 8-mph speed gain. “Realistically,” one owner told us, “this is a 150- to 160-MPH airframe and anything faster than that will require converting a lot of avgas into noise.”

Owner Gordon Nesbitt sent us this list of common modifications, at least some of which any airplane on the market is likely to have: Low drag cowlings, fully enclosed main gear doors, flush and panoramic windows, single-piece and sloped windshields, flap and aileron gap seals, tip tanks, full bubble canopies, improved cabin ventilation, retractable entry steps and Cleveland brake mods.

Some sources: American Navion Society at www.navionsociety.org or 360-833-9921. Navion Skies provides parts and support at www.navionskies.com and 209-367-9390. Another Navion support business is Sierra Hotel Aero Parts at www.sierrahotelaero.com and 651-306-1456.

Tom Deluca of Cabazon, California has parts, mods and technical support at 951-849-7594. Douthitt Aviation also has speed mods at 760-791-8807. For tip tanks and fuel mods, contact J. L. Osborne at 760-245-8477. Try Classic Aero Service, Aurora, Nebraska, at 402-694-0171 for parts, service and engine mods. Matt Jackson in Van Nuys, California (818-424-1131) does well-regarded IO-550 conversions and speed mods.

Maintenance

A buyer new to the Navion is cautioned to find a shop familiar with the airplane to do a thorough pre-buy. Although cheap to purchase, a poorly maintained example can easily offset any initial cost-of-entry advantage. Here are some hotspots to watch.

Although this one has been upgraded, modern designers could learn about panel design from departed North American engineers. The panel is spacious and well thought out, with some instruments and switches on the overhead canopy rail.

• Landing gear: These are hydraulic systems, with the usual headaches with retract links, hoses and pumps. Some older airplanes may still have the original single-piston hydraulic pumps, which should be replaced with new versions. Check for loose trunnions in the gear pivots and for play in the nosegear, causing shimmy.

• Corrosion: Like other military airplanes, Navions built by North American were lavishly zinc chromated. But Ryan cut back on chromating and that may allow some corrosion to creep it. “Remove the seats, side upholstery panels and wing root fairings,” wrote one owner, “and check for corrosion where the fuselage mounts to the top of the wing.”

• Cooling: Although most examples have probably been cured of this, early Navions had inefficient updraft cooling. The B-model with the 260-HP Lycoming has oil temperature problems easily cured with a larger aluminum oil cooler.

• Propeller: The old Hartzell diaphragm-type props used on original Navions will leak. They must be replaced and adjusted regularly, if parts are available, or the prop replaced with an STC’d upgrade. (Hartzell and McCauley offer upgrades, but not for all engines.)

• Continental E-225: These engines are somewhat temperamental, tend to leak oil and are relatively expensive to overhaul. Owners recommend upgrades instead.

Owner Feedback

Last year, my friends suggested that I buy a Cessna 182 as my first airplane, but instead I bought a 1950 Navion Model A that had been carefully restored and maintained by an A&P. Before purchasing this Navion, I acted upon the advice of AOPA, knowledgeable Navion owners and airplane owner friends, performing a title search and pre-buy inspection. I got a basically good airplane, although I would have saved money if my enthusiasm had been directed less on completing the purchase and more on learning about Navions.

I did not know enough to be careful to check the aircraft’s records for FAA field approvals for every single deviation from the aircraft’s Type Certificate, namely, installation of the wide-visibility windows, improved instrument panel, nosebowl, oil cooler, flap gap kit, rear step and more.

Missing field approvals have since been received from the FAA, enhancing the value of my airplane because so many Navions lack a complete record of approvals to modifications made over the years.

My pre-buy inspection was performed by an A&P/IA who was not familiar with the quirks of the Navion. If he had but removed the seats and carpets during the inspection, he would have discovered that someone had cut two four-inch holes under the seats to gain access to the fuel tanks, which had been leaking (as the tanks in most Navions do over time) and were illegally patched with epoxy.

Finally, if I’d been more careful in my research, I would have learned about the reputation of the engine found on my Navion A and many early Navions and Bonanzas, the Continental E-225. That engine is notorious for oil leaks, low oil pressures in warm temperatures and $25,000 overhauls. Upgrades to larger, more modern engines are available, but can cost from $30,000 to close to $50,000. A top-of-the line 310 HP Continental IO-550-R engine with carbon fiber cowl and tubular engine mounts would cost about $84,000 out the door.

Realistically, I can get 135 knots at 75 percent cruise and 13 GPH, or slow it down to 105 knots and 9 GPH. The baggage area is cavernous with two adults and a child and full tanks, it will hold more than enough and still be within weight and balance limits. The Navion’s flaps are huge, allowing steep descents to land on the numbers where other aircraft would be going around. The landing gear is of simple design, contributing to its reliability.

Excluding the costs I’ve paid remedying my airplane’s deficiencies, the cost of flying my Navion remains in proportion to the pleasure of owning it. My next annual may cost $1500 and insurance about $2200/year for hull value of $85,000.

If my Navion were a car, I suppose it would be a vintage MG sports car with panache and sex appeal. For that, who needs a station wagon?

John Leggatt, Woodland Hills, California

I have owned two Navions and both were/are great airplanes. The first was a 1947 sliding canopy model built at the North American Aviation plant in El Segundo, California. It had many upgrades including a TCM E-225 engine and a beautiful full-house IFR panel. It was also equipped with 20-gallon Brittain tip tanks. This early Navion provided totally reliable service whether VMC or IMC, and averaged 180 to 190 hours per year.

My current Navion is a 1961 model G Rangemaster powered by a TCM IO-470-H engine of 260 HP. It is fully IFR-equipped and the engine is also equipped with GAMIjectors, which have been fine tuned so I typically cruise lean of peak at a fuel burn of 11.4 to 11.7 GPH. I heartily recommend this GAMI product.

Typical LOP true airspeeds at cruise altitudes are in the range of 155 to 158 MPH. Max fuel capacity with the standard 34-gallon tip tanks is 108 gallons, which gives the Rangemaster long legs for cross-country flying. Obviously, the Rangemaster name is quite appropriate.

The last Navions built were the H-models with the TCM IO-520 engines. Production ceased in 1976, with a total of all versions (sliding canopy models and Rangemaster models) amounting to approximately 2700 units. Many of these aircraft are still flying and/or undergoing upgrading and restoration.

The Navion is a very robust, reliable airplane with a generously sized cabin and excellent visibility. Its barn-door size, single-slotted flaps and cambered airfoil provide very impressive short field performance. It’s an all-hydraulics airplane whose systems are reliable. Frequent flying keeps them that way.

In all my Navion flying hours, I have never had a major hydraulics problem. I’ve replaced a few O-ring seals in gear actuating cylinders and landing gear struts, but nothing major. The Navion is a big airplane with generous access for maintenance and maintenance that is not complex.

The model G Rangemasters were certified at a gross weight of 3150 pounds. However, with a change to an improved wing/fuselage root fairing and some other minor bits, the gross weight can be upgraded to 3315 pounds. The standard dry empty weight ( from the 1961 Owner’s Manual) for the G model is 1950 pounds, which provides a useful load of 1200 pounds.

I doubt that any currently equipped G model would have a 1950-pound empty weight. My aircraft has an empty weight of 2005 pounds, which provides a useful load of 1145 pounds. Of this, the Owner’s Manual says the baggage compartment capacity is 190 pounds and an optional full size fifth seat can be bolted into this compartment. I have this seat, but I have never loaded up this baggage area to 190 pounds.

When Navions first came out right after World War II, they were head-to-head competitors with the Beech Bonanza, but the Navion was always slower due to its cambered airfoil and taller fuselage. Over the years, both aircraft were upgraded and improved, but the Bo always had the speed advantage.

However, the roomier cabin, better visibility and rock-steady IFR flight characteristics were attractive Navion features and its short-field performance was always impressive. I have flown both Bonanzas and Navions over the years and I much prefer the Navion. The Navion is a helluva lot of airplane for the money!

Insurance costs me about $2300 annually, including full hull coverage. Annual inspections have been in the range of $900 to $1700, although I had a $3800 hit several years ago when major repair of the exhaust manifolds was required.

Joe Noyes, Irvine, California

Our 1951 B Model came with a fresh engine upgrade (TCM IO-550), a spacious leather interior, a well-equipped modern IFR panel, 2500 airframe hours and just about every speed modification currently available. With tip and auxiliary fuselage tanks we can (but rarely do) carry 100 gallons. Considering the purchase cost and avionics upgrades, we have about $145,000 invested. This is the higher end of the Navion market. More modestly equipped Navions with mid-time IO-470s, IO-520s or IO-540s commonly sell for $65,000 to $110,000.

With 310-HP up front, getting ours off the ground requires some heavy pedal action to overcome P-factor during the first 300 feet of runway. In flight, the aircraft is very stable and has been a great IFR training platform. Slowing down for an approach is complicated by the fact that max gear extension speed and deployment speed for max flaps are both only 100 MPH. While you can start staging flaps at higher speeds, don’t plan to use the gear or full flaps to get that speed down. Properly trimmed, landings are no-brainers.

Based out of San Diego, we typically need to get above 7500 feet just to get out of the neighborhood. At that altitude, we cruise at 21 squared and see an IAS of 150 to 155 knots with a LOP fuel burn of 9.2 to 9.5 GPH. Down low, level and rich, she will easily push past Vne if you’re not watching closely.

Short field-performance is astounding. With those barndoor flaps, the Navion is capable of unnervingly steep approach angles and short roll-outs. We’ve been fully loaded and had no issues getting in and out of very rough and short back-country strips.

Navion-experienced IAs have performed our annual inspections and I have taken the hands-on owner role for most of our maintenance needs.

Consequently, our annuals have typically run between $1000 and $1200. The IO-550 now has about 500 hours and other than replacing the starter drive adapter, maintenance has been limited to plug, oil and filter changes.

We have had no major issues with hydraulic systems. Most parts are readily available from the American Navion Society, Sierra Hotel Aero (Type Certificate holder) and several PMAs and OEM parts distributors specializing in Navions.

Gordon Nesbitt, Oceanside, California

Like many other Navion owners, I fell in love with the bird at first sight. There’s nothing that looks quite like a Navion. The lineage visibly traces back to the P-51 Mustang, also a North American design. Most reviews I initially read said the Navion is heavy and slow, although very stable, with fine flying characteristics. It took me a while to work through the chaff and discover that there are many 310-HP conversions out there that are fully certified also. These airplanes will cruise between 160 and 165 knots.

I have a canopy Navion with a Lycoming IO-540 290-HP engine installed under a field approval in Canada some years ago. With tip tanks at 20 gallons each, I have 80 gallons total. I’m typically off the ground in 700 to 1000 feet, climb at 800 to 1000 FPM from sea level and cruise at a reliable 140 knots. These are not, however, usual numbers for a Navion. A purchaser with a cruise speed requirement to fulfill is well advised to fly speed trials in the candidate airplane before purchase.

The Navion sits tall on three oleo-strutted gear legs. It’s a long climb onto that high wing. This is a 1946 Navion A owned by Martin Vargas, of Jupiter, Florida.

The Navion sits tall on three oleo-strutted gear legs. It’s a long climb onto that high wing. This is a 1946 Navion A owned by Martin Vargas, of Jupiter, Florida.

With my 80 gallons at 70 percent power, I burn 12.5 GPH and can do 700 miles with generous reserves. With the fat wing, the heavy gear and larger tires, I can get into and out of just about any short/soft strip in the country. The airplane is not light, allowing about 3100 pounds max gross weight. With full fuel, I can carry three people plus maybe a little baggage. With four hours fuel plus reserves, I can fill the seats.

The flying characteristics are very stable. The Navion is an excellent instrument platform. I’ve been through turbulence that would have had a 172 doing aerobatics—the Navion just bumped a lot.

Gear extension speed is low at about 100 MPH. However, with the fat wing and a touch of flaps, she slows right down when the power is backed off. Full flap extension requires substantial pitch trim, but not as bad as the EADS Trinidad I used to rent. Flap extension is also continuously variable on most aircraft, so I use just enough. Stalls have to be forced and even then are really just a mush with a moderate sink rate. Recovery is immediate. There is no tendency to roll.

As a first-time owner with 300 hours, 60 hours of retract time and a straight private license, I had to pay $4000 for my first year of full coverage. That’s dropped nearly 25 percent in the second year. My only annual so far ran about $1000. Not bad for an airplane that does everything a 182 can, but with more panache.

The cabin is widely accepted as the most spacious and comfortable available in piston singles. Temperature control is a problem in many Navions, with the front seats cooking while the rear seat freezes. Proper attention to sealing leaks around the canopy and wing attach points are said to help this problem.

Trunnion bearings on the main gear should be checked by a Navion mechanic before purchase. The overhaul of these bearings—which will last a long time if not abused—is not inexpensive. Other pre-purchase items also worthy of review include wing tanks for leaks, hydraulic system for proper operation and airframe for corrosion.

I bought my Navion for its versatility. It has great back-country abilities, but cruises fast enough to use in distance travel. It’s comfortable, inexpensive and fun. Aw, heck. Who am I kidding? I bought it because I like the way it looks!

Case Ketting, via e-mail

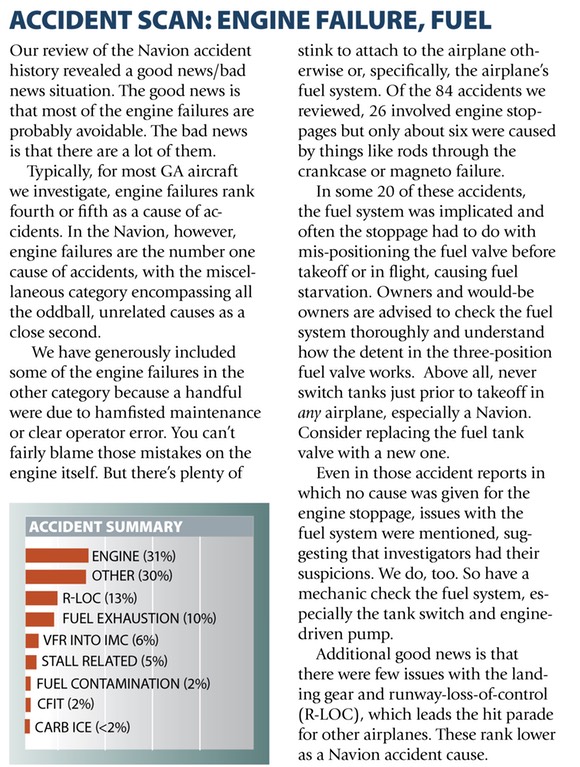

Accident Scan: Engine Failure, Fuel

________________________________

A Most Dignified Way to Travel

by Rick Durden

The Navion is wondrously easy to fly, amazingly stable, and capable of stunning short-field work.

Overbuilt, slow, but a joy to fly

It just wasn't as fast as it looked. This sad, true, but overly simple phrase is the requiem expressed by those who have not learned the secrets of the Navion. To those fortunate enough to own and fly them, Navions are arguably the best-handling and most comfortable retractable singles ever built. So much so that Bonanza owners, who fly very good airplanes in their own right, have been known to walk away after a Navion flight muttering, "At least mine goes faster."

Fresh from building some remarkable airplanes during World War II and soon to turn out the F-86 Sabre — a jet fighter still beloved for its handling — North American Aviation Inc. took a deep breath and entered the postwar general aviation sales fray. It chose to build one of the few four-place retractable singles to hit the market. The Navion did well in its first year, 1946, but faded after the Beechcraft Bonanza was introduced and its impressive speed became apparent. North American, perhaps prescient in recognizing the degree to which people would willingly cram themselves into tiny spaces for the sake of speed, sold the design and many completed parts to the Ryan Aeronautical Corporation (now Teledyne Ryan), leaving the general aviation field for other endeavors.

When one views the lines of a Navion, with its sliding canopy, the P-51 Mustang heritage is obvious. Interestingly the more apt comparison among products from the North American drawing boards is with the B-25 Mitchell. Like the Navion, the B-25 was not fast, but wondrously easy to fly, amazingly stable, and capable of stunning short-field work, as a certain lieutenant colonel with the wildly inappropriate name of Doolittle demonstrated in early 1942. The only difference was that the B-25 was very heavy in roll, while the Navion is not.

North American had figured out the benefits of tricycle gear on the B-25 years earlier, so the fact the Navion was not equipped with a tailwheel surprised no one. Quite striking are the length of the landing gear legs and the resultant propeller clearance from the ground. The beefy gear struts absorb some impressive shocks on landing, a legacy of a desire to be able to alight almost anywhere, and perhaps to convince skeptics that a nosewheel airplane was suitable for unimproved fields. Instead of the Mustang's laminar-flow airfoil, the Navion has a high-lift, high-drag wing with significant camber on the underside. The combination of the specialized wing and flaps with 45 degrees of travel resulted in nearly legendary short- and rough-field ability for a 2,850-pound airplane. It also created a lamentable cruise speed of only 120 knots on 185 horsepower (205 for takeoff) and, later, 225 hp.

Part of the reason for the aircraft's durability and its ability to absorb punishment is that it was substan-tially overbuilt. North American sought to sell a great many to the military, so military requirements figured prominently in the design. It did sell to the military 250 of the 1,100 it built, so the type is a legitimate warbird.

In 1948 Ryan took over and built the "A" model for three years, producing about 1,200 airplanes. The type certificate then began a process of changing hands. Versions of Navions with increasing horsepower; doors instead of a canopy; and more fuel capacity — but not much more speed — were built in fits and starts through the mid-1970s.

There seem to be more aftermarket modifications out there for the Navion than for virtually any other airplane, making an original Navion very hard to find. Speed mods prevail, yet the more realistic owners admit that it is difficult to eke out much more than about 10 kt even with all the mods.

From anecdotal evidence, the utterly delightful handling of the Navion has consistently had a most interesting effect: Numerous owners claim to have made their purchase decision after but one flight. For a certain proportion of the pilot population, speed is easily traded for comfort, handling, and incredible toughness.

Walking toward a Navion, one is first struck by the height of the airplane. The wing hits a person at mid-chest level. The lines are relatively clean, but there are also jarring inconsistencies. The vertical tail appears to be abruptly truncated. While tail area is more than adequate because of its long arm, it had to be short enough to fit through the door of a T-hangar. The many-paned windows are held in with large, unsightly rubber gaskets that reduce manufacturing time, but are drag incarnate. Most owners have modified their airplanes to remove the gaskets, as well as gone to a one-piece windshield.

On most Navions, boarding is via a step which juts from the leading edge of the wing — causing one to hope that Navion pilots always shut down the engine before loading or unloading passengers, given the proximity of the propeller. Sliding open the canopy is surprisingly easy. It glides on heavy-gauge rails, another example of the build-it-solid design philosophy applied to the airplane. On opening, the canopy takes with it the headrests for the rear seat and exposes the baggage area. Loading baggage means hauling it up and into the cabin, then heaving it over the rear seats — not an easy task. A popular aftermarket mod is a left fuselage baggage door. The rear seats do fold forward, so that one can get at baggage while in flight.

For a complex airplane, preflight is easy. Flap hinges and the actuators for the flaps hang well below the lower surface of the wing, adding drag but making inspection a snap. The cowling opens up to expose the entire engine compartment, allowing one to also inspect the hydraulic pump and hoses. The original rigid hydraulic lines had a reputation for breaking. Once owners switched to flexible hoses, problems diminished. A willingness to do routine preventive maintenance seems to keep the hydraulically powered landing gear and flaps happy. Should a hydraulic line break, owners report that the gear will extend, thanks to some large springs that are part of the aircraft's emergency gear extension system. It takes but a bit of rudder-pedal-induced yaw to snap the mains to a locked position while the nose gear takes care of itself.

Boarding is challenging the first time. Left foot on the step, left hand on the fuselage handle — followed by a step up with the right foot to the wing. Step over the canopy sill and down to the floor behind the front seats. Next, work your way forward between the seats to the command spot. Once you are ensconced, the position is more comfortable than that in almost any other airplane built. Fore and aft seat adjustment is more than adequate for the full range of pilot physiques. The instrument panel starts directly under the windshield, with no glareshield at all, a somewhat novel feature that keeps one from putting something metallic next to the compass. Seated, you are at the leading edge of the wing — which, together with a nose that slopes sharply downward, makes for extremely good visibility. The rear-seat occupants sit higher than those in the front, again quite rare. This movie theater approach makes every seat in this house a great one.

The fuel system has 20 gallons in each wing and 20 gallons under the rear seat, although there are modifications to add more with tip tanks. At about 12 gallons per hour, endurance isn't bad. While the idea of fuel inside the fuselage can be a bit disconcerting, the rugged construction of the airplane helps to protect the tank from breaching in a crash.

Startup, per the checklist, involves pressing the foot starter, letting the prop go through four revolutions, then turning the ignition switch to the Both position. Sadly, most of the foot starters are long gone, so internal combusting now comes about from the ubiquitous ignition key's being turned to the Start position. A certain panache was lost with that "improvement."

The ride while taxiing offers a very noticeable indication that this airplane is unlike others. The gear absorbs bumps and potholes, providing a solid ride so deceptive that owners have damaged nose gear legs by taxiing too fast on rough surfaces simply because they did not realize how bad the surfaces truly were.

Runup reveals nothing very unusual, although because of the instrument locations, it may take a while for the new pilot to find the appropriate gauges.

Takeoff is the next pleasant surprise. Acceleration is smooth and rapid; the 48-kt rotation speed shows up quickly. The airplane launches in 500 feet or so, then climbs nicely at 70 kt. Should obstacle clearance be of interest, 20 degrees of flaps is used with 61 kt on the airspeed indicator. To retract the gear, it is first necessary to activate the hydraulic system with one knob, then raise the gear with another. Once the gear has finished its cycle, the first knob is moved again to deactivate the system. According to owners, this extra bit of work — also required for flap operation — soon becomes second nature.

In addition to making the airplane very stable by using substantial dihedral, it soon becomes apparent that North American engineers knew how to design controls that were well-harmonized in all axes and are also very responsive. Control responsiveness and stability in cruise often seem to be mutually exclusive, yet the designers paired the two well on the Navion. Instead of wagging its tail in turbulence, it resists displacement, riding out the bumps with a minimum of dislocation. The rudder-aileron interconnect system means that coordination in a turn is nearly effortless. Slow flight is second nature for the highly cambered wing, with all flight controls retaining authority through the very docile stall. Steep turns are without vice.

Sitting in the captain's seat in cruise, you cannot help enjoying the manner in which the Navion rides as the landscape rolls serenely by. This airplane simply defines dignified air travel. The sails are set. The breeze is freshening. The world beckons. To hell with the numbers on the airspeed indicator.

Far too soon, a flight in a Navion draws to a close. Should an instrument approach to a landing be chosen, it may be measured in yawns. Because of its stability and smooth control response, the airplane is an ideal instrument platform. Pilots new to Navions set things up, intercept the final approach course, begin tracking inbound with minimal fuss, and then wonder if they have missed something. The workload involved in keeping other airplanes pointed in the desired direction on approach simply is not present in the Navion.

The one shortcoming that does become apparent is the painfully low speed for landing gear and flap operation — only 87 kt. Navion pilots become masters in negotiating with ATC for lower altitudes early so that they can put the gear down before reaching the destination airport. Even for VFR flight, this limitation means that a pilot has to do some planning for the arrival. For while the Navion is not fast in cruise, it is also unwilling to slow down to landing speeds when the time comes.

Once the hydraulic system has been cycled on and off in the process of lowering the gear and extending the flaps, the approach path can be shockingly steep. With a final approach speed of 61 kt and massive flaps, it is easy to land in places from which the airplane cannot depart under its own power. The military-inspired gear will absorb most goofs nicely, further adding to the fascination that so many have with this machine. The Navion is one of those rare airplanes that turns a simple flight into a sensuous event.

From a nuts-and-bolts point of view, the structure is built overly strong; the systems are pretty straightforward; it has few problem areas; and it is probably the only airplane born of its era to have a decent owner's manual — printed in color and spiral-bound, no less. New, the Navion was a full cut above the tube and fabric tailwheel airplanes that were offered by so many at the time. It attracted those service pilots returning to the civilian world from heavy iron and unwilling to putt around in aircraft subject to every tiny gust. It carried a decent load and handled better than any general aviation airplane at the time. Yet, it committed aviation's mortal sin: It was slow.

One year after the Navion debuted, the faster Bonanza appeared, costing no more to maintain and feed than the Navion. The result was inevitable. The Navion now occupies that special niche for discerning owners who demand handling and comfort and forgive the sedate manner in which it traverses the sky.

June 1, 1999

Source: http://www.aopa.org/News-and-Video/All-News/1999/June/1/Navion.aspx

1948 Navion with split windshield